We are amid a revolution in nicotine technology. Thanks to massive investments in research and development, patents are being filed at a dizzying pace and the ramifications of this IP are being felt in the real world. Already, 100 million people are using harm reduction products (HRPs). And projections suggest that, if these tools are more widely adopted, as many as three to four million lives could be saved annually by 2060. Indeed, some parts of the tobacco and nicotine industry are transforming in ways that would have been unthinkable just two decades ago. Correspondingly, our cultural and political attitudes toward the contributions of industry must shift.

Even as bodies like the USFDA and Cochrane recognize the value of new HRPs, the technology faces strong headwinds. Disinformation about nicotine and the alleged effects of e-cigs have led to policies disfavoring HRPs, and to a public discourse that denies its benefits. Moreover, many governments now regulate nicotine HRPs in a manner that is inversely proportionate to risk. In Australia and India, for example, policy is more hostile to lifesaving HRPs than to deadly combustibles.

Policy has, in too many instances, lost touch with science.

Through serious investment in innovation, industry has created tools that have the potential to help create one of the most profound public health shifts in history: the elimination of combustible cigarettes. Yet, in many respects the deck appears stacked against change. It’s difficult enough to nudge tobacco control groups away from the status quo—let alone to urge the embrace of solutions arising from industry. Indeed, if we are to finally end the use of toxic tobacco products, it will be necessary to unlearn decades of industry demonization and embrace what the science is telling us: harm reduction works.

In short, the present technological revolution demands an accompanying ideological revolution.

Currently, many in the tobacco control community are skeptical, even hostile, toward the contributions of industry. The origins of this hostility are not terribly difficult to identify. For generations, the tobacco industry has created products that have killed millions of people. On top of that, industry actors have repeatedly proven themselves dishonest when it comes to scientific research practices.

A notable offense came in 1954 when a group of tobacco companies published “A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers” in some 400 American newspapers. Anything but frank, the ad claimed that there was a lack of scientific consensus regarding the health risks of smoking and no proof that the habit was responsible for increasing rates of lung cancer. Promising to further investigate these claims, the industry also announced the formation of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee—effectively a PR effort aimed at confusing public understanding of tobacco science.

This is what “industry science” meant during the second half of the 20th century: a series of schemes devised to distract and confuse smokers regarding the deadly consequences of using combustible tobacco. No amount of PR obfuscation could hide the devastation caused by tobacco in the long term. Sir Richard Peto estimates that a billion people will die this century from tobacco use. The stakes could not be higher.

As part of the US Master Settlement Agreement of the 1990s—between American tobacco companies and Attorneys General from 46 States—the industry was forced to disband its so-called research groups. The settlement marked the beginning of a new era in the treatment of industry and the endeavors it funds, including and especially research.

Throughout the nineties and into the new millennium, anti-industry attitudes and policies became the default. In 2005, the World Health Organization codified this stance via its Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the implementing guidelines of which state that, “There is a fundamental and irreconcilable conflict between the tobacco industry’s interests and public health policy interests.” Today this assumed conflict is often cited as justification for a hostile attitude toward all things industry.

Over the past two decades, thoughtful and justified actions against industry evolved into perfunctory bans, boycotts, and attacks. Ironically, attitudes grew more outwardly antagonistic during the very period in which industry began making positive contributions to the field of tobacco control.

I want to be very clear: I am under no illusion that the tobacco industry suddenly saw the light and decided

to act for the benefit of humanity. Rather, following the events of the nineties, industry did what was necessary to survive. Recognizing a public desire for safer nicotine options, some tobacco executives began prioritizing research into HRPs—products that, at least among a few companies, had been in the works for decades but only placed on the front burner at the turn of the century. A few companies made a bet that investment in HRPs would pay out in the long run. This was a shrewd business decision—and, incidentally, it is proving to be an excellent contribution to science and health. Though the transition to safer products remains incomplete, many tobacco companies have diverted resources away from combustibles and toward reduced-risk portfolios. For example, the smoke-free portfolio of Swedish Match accounts for over 70% of its operating profit. Similarly, according to recent reports, 28% of PMI’s revenue comes from its heated tobacco product, IQOS—and the company hopes that number will reach 50% by 2025. Notably, this represents not merely a gradual transition away from legacy tobacco products, but rather the cannibalization of an iconic combustible brand.

The start to transformation of the legacy tobacco sector is complemented by innovation among players who started with no tobacco roots. In the United States, JUUL is the most notorious of these companies. In China and Singapore, e-cigarette companies Smoore and Relx have dominated innovation. Though free of the dirty reputation of legacy brands, these companies are responding to the same market demand: consumers want nicotine products that are not deadly. In this regard, the business goals of these new companies align with a public health goal—namely, to destroy the combustible tobacco sector.

The "fundamental irreconcilable differences" between the interests of tobacco companies and public health are giving way to more nuanced realities.

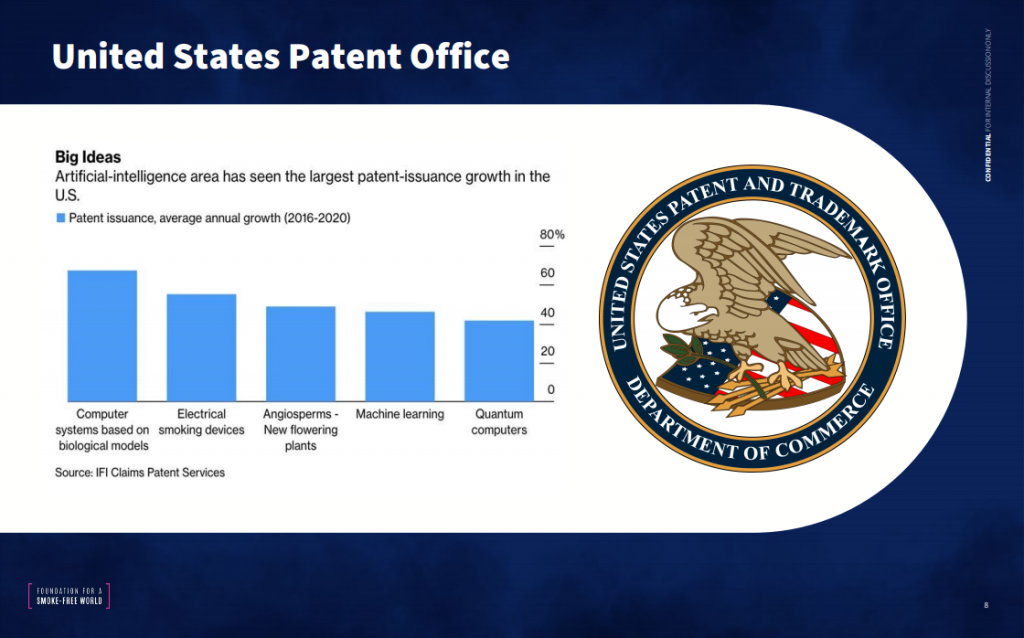

Though one might expect the broader public health community to embrace novel nicotine solutions, the response has been mixed, to say the least. This is due largely to entrenched hostility toward industry, as well as the fact the tobacco control community simply did not anticipate industry innovation. Meaculpa. Upon recently reviewing the FCTC text, I was surprised to see that that we failed to mention the importance of intellectual property or patents even once. Then, we doubted that a dirty legacy industry would invest in serious R&D. We were wrong. And the latest report from the US patent office and a forthcoming review of global patent filings in the sector underscores just how wrong we were.

The first of its kind, this new report documents major innovation in three areas over the past decade: First, it shows that, within large state monopolies, research has focused on improving consumer experiences of combustibles—a trend that will keep the death rates high. Second, the report reveals that HRP innovation is being led by a small number of multinational tobacco companies, along with China- based e-cig companies; and finally, it indicates that some multinational tobacco companies are filing patents aimed at developing new therapeutic options for health derived from recent R&D progress.

In many respects, the nicotine industry now functions in a manner similar to the pharmaceutical industry. To be sure, they’re self-interested and profit driven. At the same time, however, they are leaders in scientific

innovation and essential to overcoming massive health crises. This “Pharmaceuticalization” was aptly summarized in 2017 by Yogi Hale Hendlin and colleagues, who describe the phenomenon as: “the tobacco industry’s actual and perceived transition into a pharmaceutical-like industry through the manufacture and sale of noncombustible tobacco and nicotine products for smoking cessation or longterm nicotine maintenance.”

"the tobacco industry's actual and perceived transition into a pharmaceutical-like industry through the manufacture and sale of noncombustible tobacco and nicotine products for smoking cessation or long-term nicotine maintenance."

Dr. Yogi Hale Hendlin

Whereas Hendlin somehow casts this pharmaceuticalization as a bad thing, I take the opposite view. Tobacco companies have, in the past few years, conducted fundamental clinical, and epidemiological research that will be necessary to optimize the safety, efficacy, and desirability of new HRPs. And, like a pharmaceutical company, they are completing these exhaustive studies to meet the scientific standards set by major regulatory bodies— starting with the FDA.

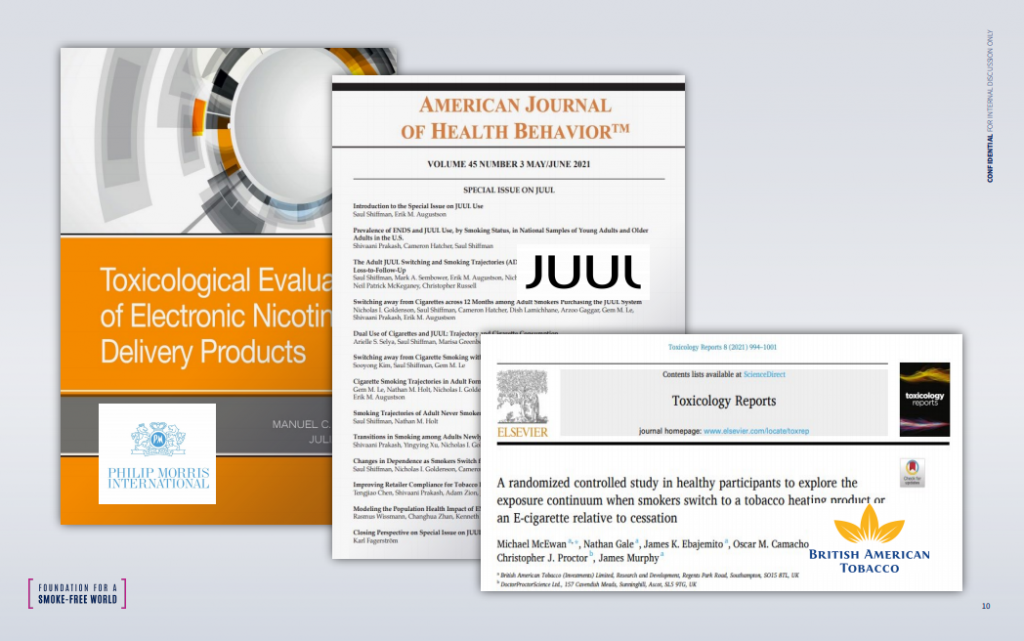

To satisfy the FDA’s strict rules of evidence, tobacco and e-cig companies have conducted extensive, peerreviewed research and have disseminated these findings via monographs and reports. American ecigarette maker JUUL, for instance, recently compiled their latest peer-reviewed research in a special edition of the American Journal of Health Behavior. Similarly, PMI has released a monograph that synthesizes their research from the past decade. Taken together with publications by other companies, the work amounts to a robust and growing body of evidence that confirms the health benefits of HRPs.

The tobacco industry knows the reputational hurdle it must overcome and, as a result, has some of the most robust safety and toxicological data that exists.

According to Foundation analyses, PMI and BAT have published more papers on heated tobacco products than any other research group. Combined, the two companies have in fact published more than the sum of the next 13 entities, which are leading universities. The FDA cannot and does not ignore this evidence.

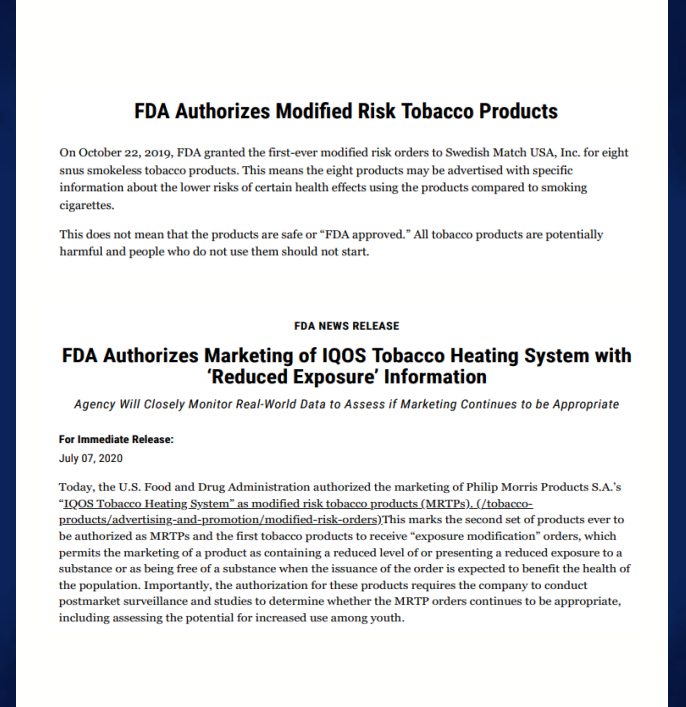

In October 2019, the FDA announced that Swedish Match USA would be authorized to market its smokeless tobacco as a “modified risk tobacco product.” In July of last year, it authorized the marketing of IQOS with “reduced exposure” information. This latter decision arrived three years after the company shared over one million pages of documentation. Further, the authorization was granted under the provision that Philip Morris would conduct post-market surveillance to ensure that the products indeed reduce risk and, critically, are not used by youth.

Notably, the FDA’s “exposure modification” orders,

which “permit the marketing of products as containing a reduced level of or presenting a

reduced exposure to a substance or as being free of a substance,” were made because the products are “expected to benefit the health of the population.” See FDA July 2, 2020 Announcement. These statements represent yet another clear challenge to the “irreconcilable difference” clause used by WHO to justify a stubbornly undifferentiated anti-industry posture.

These authorizations mark an important step in increasing the availability of HRPs—and the FDA’s stamp of approval should inspire global confidence in the state of HRP science. Sharfstein et al have highlighted this point in their discussion of US vaccine approvals and elsewhere. They note that the standards of the FDA are so high—and their efforts so transparent—that its endorsement commands unique respect. The evidence in favor of HRPs has also been acknowledged by Cochrane and the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), which hold similar standing in the UK. In almost any other context, these votes of confidence would count as definitive. Yet, because a large portion of HRP research comes from industry, many still classify the research as “controversial.”

All bodies following the science appear to have arrived at the same conclusion: HRPs can play an important role in combatting the world’s tobacco crisis. By contrast, institutions attached more to ideology than evidence remain opposed to innovation in this space. Among those in this camp are journals and academic groups that repeatedly boycott or ban industry research.

In 2013, for instance, BMJ group announced that its journals would “no longer consider for publication any study that is partly or wholly funded by the tobacco industry.” Similarly, CRUK, Wellcome Trust, and SAMRC developed policies that bar collaboration with industry-funded scientists. As a result, harm reduction researchers are often excluded from influential meetings, journals, funding opportunities and institutions.

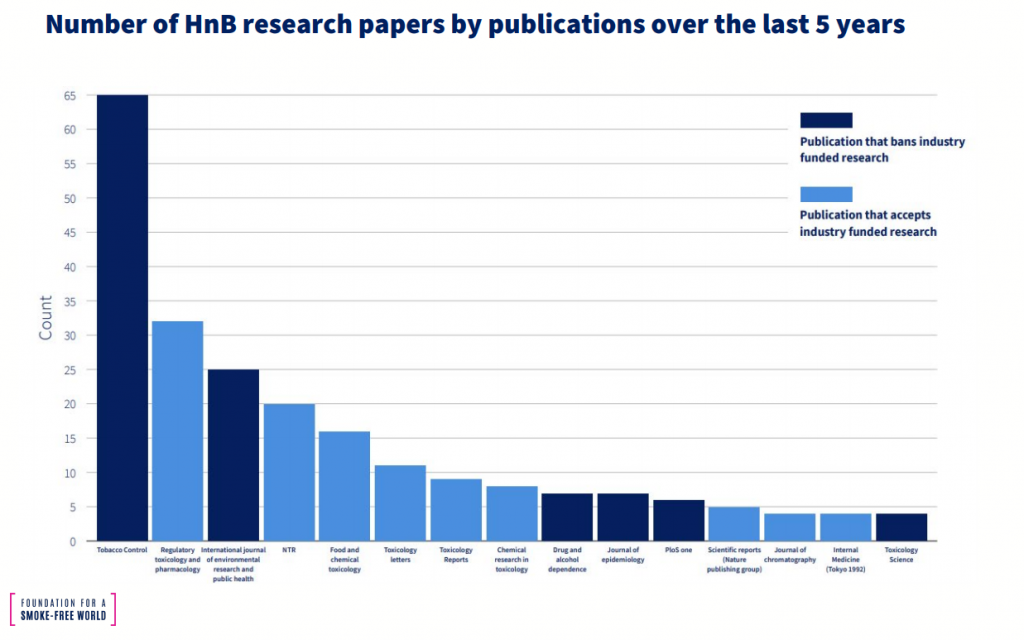

Indeed, there now exists two distinct silos in tobacco research: one in which the evidence for harm reduction is robust and growing; and one in which such evidence does not exist. Foundation analyses of publication trends underscore these parallel universes. Papers in Tobacco Control, a BMJ journal, come exclusively from academics. Due to bans, none come from industry. By contrast, 95% of papers in Regulatory Toxicology and pharmacology are from industry. This leads to serious publication bias.

In some cases, opponents cite clause 5.3 of FCTC to justify the wholesale rejection of industry research. This clause is appropriately intended to prevent conflicts of interests among parties to the FCTC— which is to say, among governments. Yet, it has been invoked time and again to justify the banishment of industry-funded people and organizations from a variety of settings where they might make desperately needed contributions.

These misuses of 5.3 persist despite very clear implementation guidelines, which stress the need for accountability and transparency in parties “when dealing with the tobacco industry.” These guidelines do not mention bans, prohibitions or boycotts. And they certainly don’t endorse the harassment of scientists—an abuse too-often endured by industry funded researchers and others in the field of harm reduction.

These practices run counter the principles of open science that, increasingly, are being embraced by researchers, institutions, and nations. For example,the American Library Association’s Bill of Rights states that “Materials should not be excluded because of the origin, background, or views of those contributing to their creation”; and UNESCO’s recommendations on Open Science emphasize the importance of inclusiveness, collaboration, and respect.

"Materials should not be excluded because of the origin, background, or views of those contributing to their creation".

American Library Association

Ad hominem attacks on industry researchers are unacceptable. In addition to lacking in integrity, these practices impede the adoption of measures that could save the lives of current smokers. Clinicians and policymakers need easy access to the full body of science if they are to make informed decisions about clinical care and public policy. As such, regressive anti-industry policies rob experts of the evidence they need to do their jobs.

Despite these headwinds, I remain hopeful that the tide will turn, as it always does.

One benefit of the outcry against industry and HRP science is a reciprocal defense of this research. Forced out of the shadows, harm reduction and industry scientists are now speaking publicly about the value of their research. For instance, writing in the journal Addiction, John Hughes and colleagues confidently describe why they work with industry. They write: “the goal of tobacco/nicotine science should be a reduction in tobacco-related morbidity and mortality… harm reduction products can play a major role in achieving this goal.”

"the goal of tobacco/nicotine science should be a reduction in tobacco-related morbidity and mortality... harm reduction products can play a major role in achieving this goal."

John Huges and colleagues

Additionally, in recent months, courageous academics and young researchers have called for an end to the schism between those supporting HRP research and wedded to the status quo. For instance, Cliff Douglas believes “it is time to act with integrity and end the internecine warfare over E-Cigarettes.” Similarly, Donna Carroll and a group of young colleagues worry that “the continued promotion of select, polarized stances on e-cigarettes will threaten the integrity of research.” And Tamar Antin and colleagues recently noted “that ignoring the potential benefits of harm reduction strategies may unintentionally lead to an erosion of trust in tobacco

control among some members of the public.”

Select publishers are also playing an active role in closing the gap. For instance, the president of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT), Megan Piper, has described a “both-and” approach to industry research. In a 2020 statement, she wrote: “SRNT is BOTH a scientific society committed to the open exchange of science AND a society that recognizes the harms from commercial combusted tobacco use and the industry whose goal is to profit from addiction to these products.”

Finally, some scholars are breaking down research silos by working with researchers from the “other side.” For instance, leading academics (e.g., David Abrams, Ray Niaura and David Mendez) recently teamed up with industry scientists to co-author a paper on the “Population Health Impact of Recently Introduced Modified Risk Tobacco Products.” Published in Nicotine and Tobacco Research, the paper represents a model of collaboration that places the attainment of health goals above unscientific quibbles.

More such collaborations will be necessary if we are to finally dissolve ideological biases and realize the full public health potential of HRPs. Here, we needn’t long vaguely for folks to come around, but rather can take practical steps to promote science-based thinking. To this end, Glynn et al recently described a practical “path forward.” Their guidelines state that the tobacco control community should focus on eliminating combustible cigarettes, which clearly pose the greatest risk to health.

"Nicotine, though not benign, is not directly responsible for the tobacco caused cancer, lung disease, and heart disease that kill hundreds of thousands of Americans each year...

To truly protect the public, the FDA's approach must take into account the continuum of risk for nicotine-containing productsGottieb and Zeller

This approach coheres with that of Gottlieb and Zeller, who in 2017 proposed a “nicotine-focused framework for public health.” They write: “Nicotine, though not benign, is not directly responsible for the tobacco-caused cancer, lung disease, and heart disease that kill hundreds of thousands of Americans each year…To truly protect the public, the FDA’s approach must take into account the continuum of risk for nicotine containing products.” Words that echo the insights and life’s work of Michael Russell 4 decades ago.

In addition to these guidelines, we now need a “Frank Statement” for our times—a commitment from all parties to prioritize the end of the tobacco epidemic. This would entail five key commitments.

1. Industry must commit to ending the sale of combustible cigarettes.

2. Industry must commit to ending youth nicotine use in all forms.

3. Industry must commit to sharing IP with companies currently selling combustibles in LMICs.

4. The WHO and governments must commit to revising the FCTC to explicitly build a risk- proportionate regulatory system.

5. Leading cancer, tuberculosis, lung, psychiatry, and heart NGOs must commit to science- based strategies for ending smoking among high-risk patients.

All of the above is feasible. It merely requires a will to take action. From a scientific perspective, the hard work has already been done. What remains, then, is the bigger challenge, which is changing cultural and political attitudes.

© 2023 Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. All rights reserved.