Continued from Part One, Searching for ‘patient zero’

This three-part series is based on an independent analysis of 18,000 news stories covering EVALI – an outbreak of vaping-related lung injuries that occurred in the United States in 2019. Part one of this series explained why the most reasonable explanation for the EVALI outbreak is an adulterant that entered the unregulated illicit THC vape oil supply chain in early 2019. Part two (below) explores how the outbreak was misdiagnosed in the US, and how that misdiagnosis spread to other countries.

Part Two: The misinfodemic spreads

United States (‘patient zero’)

In August 2019, some US media outlets began to express concerns over the wording of alerts issued by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC alerts focused on “e-cigarettes” rather than THC vaping. On August 28, for example, USA TODAY published a story with the headline, “People are vaping THC. Lung injuries being reported nationwide. Why is the CDC staying quiet?”

On August 31, tobacco harm reduction expert Jim McDonald noted that the latest official US government statement on EVALI mentioned the word “e-cigarette” 22 times. McDonald wrote, “many cannabis oil users would not even recognize that term as applying to the products they use, which are typically called oil cartridges, vape carts, THC carts, vape pens, [or] weed vapes.”

Public confusion is one obvious symptom of the EVALI misinfodemic. A January 2020 US poll found that “just 28% of adults think people have died from lung disease related to using THC products,” while “66% of adults say e-cigarettes are ‘very harmful’ …up 8% from September 2019.”

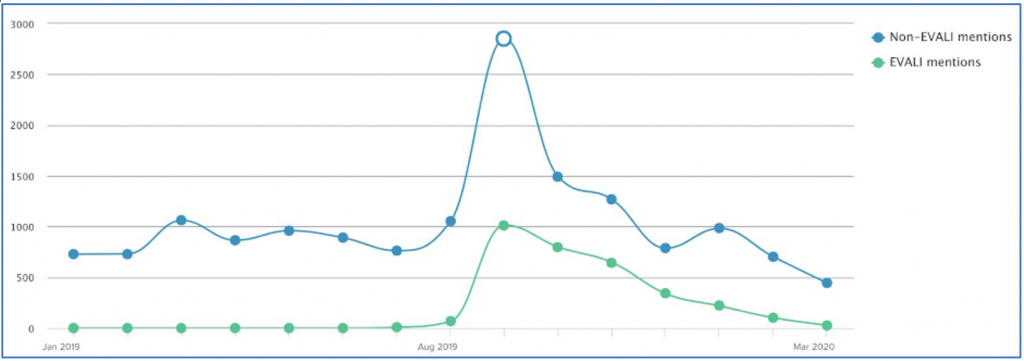

By February 2020, 68 Americans had died and more than 2,800 had been hospitalized. The tone of EVALI media reports across the countries we analyzed was, unsurprisingly, negative. However, our analysis shows an odd three-fold spike in mentions of “nicotine” coincident with EVALI mentions. This spike is odd because most evidence indicates that nicotine had nothing to do with the EVALI outbreak (see Part One of this series).

Mentions of the terms “nicotine” or “EVALI” in top-tier media reports from the United States, the United Kingdom, India and South Africa (“top-tier publications” include those with at least one million unique monthly visitors). Data from FSFW analysis.

Google trends show an approximately 20% increase in “THC” searches in September 2019. But for the remainder of 2019, “THC” searches dropped below average levels for the first half of the year. This is odd because all evidence pointed to illicit THC vaping as the cause of EVALI (see Part One of this series).

Our analysis found that in the United States, during an outbreak of lung poisonings caused by bootleg THC vaping products, nearly half of all EVALI news stories referred to a teen nicotine “vaping epidemic.” Nearly half suggested bans on “e-cigarettes,” and about 25% noted that nicotine is “highly addictive.” Most stories either failed to mention THC or buried what should have been the lead at the end. This included stories in most major US news outlets.

Below, I will explore how the US “EVALI” misinfodemic spread from that US misdiagnosis (see Part One) to the United Kingdom, India and South Africa.

United Kingdom

During the first half of 2019, media coverage of nicotine vaping was almost entirely positive. Many stories covered a February 2019 Public Health England (PHE) e-cigarette “evidence update,” and reiterated the PHE evidence review finding that nicotine vaping is at least 95% safer than smoking combustible cigarettes.

The tone of UK media coverage changed when US EVALI stories appeared in July 2019. Our analysis found that in the latter half of 2019, an increasing number of news articles sounded alarms about nicotine vaping. For example, “Vape at your peril” and “Shocking scans show how vaping e-cigarettes left a 19-year-old’s lungs filled with solidified oil that looked like hardened bacon grease.”

At the height of the US EVALI outbreak, UK health authorities issued repeated assurances that nicotine vaping is safer than smoking in September and October. These official assurances were carried in the UK press. An April 2020 piece in Health Affairs discusses such efforts by UK health officials to counteract growing public misperceptions.

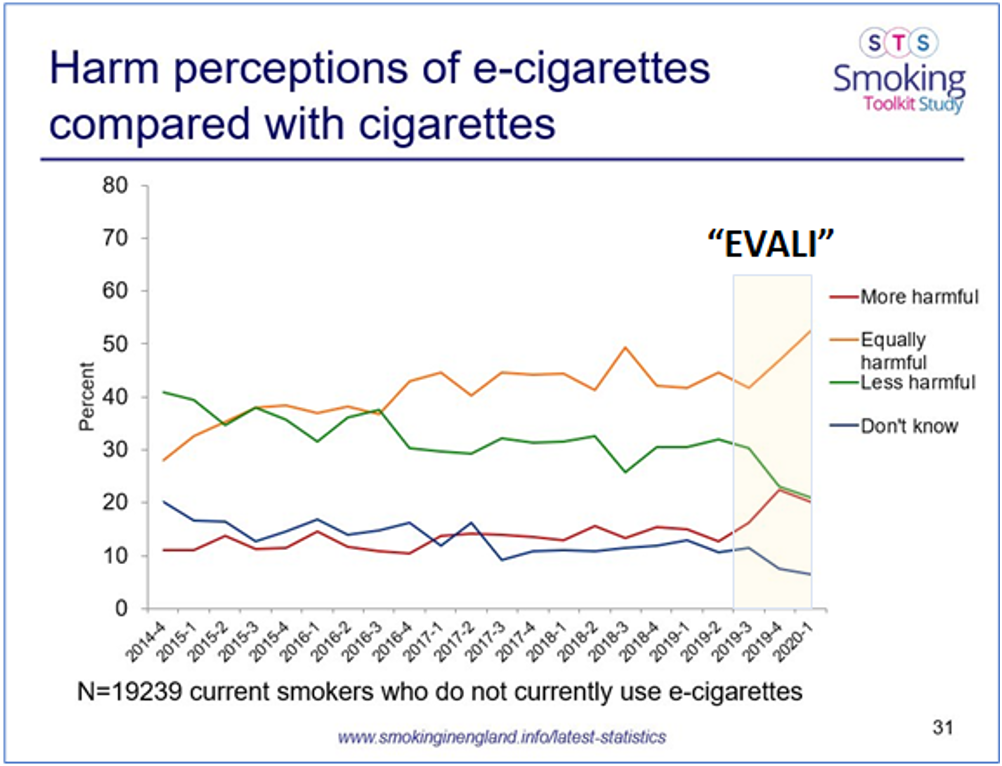

But the damage was done. In March 2020, The Independent reported on increasing misperceptions, noting that “over a third of smokers in the UK believe that e-cigarettes are equally or more harmful than combustible tobacco.” The number of people who believed that e-cigarettes were less harmful than smoking had also dropped.

UK Smoking Toolkit Study: Misperceptions of the risks of legal nicotine vaping increased, coincident with media reports of lung poisonings caused by illicit THC vaping in the United States.

India

Half a world away, lung poisonings caused by illegal THC vaping in the United States sparked “spontaneous” efforts to ban nicotine vaping in India. But India’s media sentiment toward nicotine vaping had already been consistently negative before mid-2019.

In March 2019, thousands of doctors somehow spontaneously wrote to India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi asking him to enforce the country’s advisory against on electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). In May of the same year, their message was echoed in another spontaneous letter from school students and teachers, and in additional letters from 90 public health organizations. The Indian Council of Medical Research issued its formal recommendation to ban ENDS in June of 2019.

Although the number of Indian news reports on the US EVALI outbreak spiked in September 2019, our analysis found that about half of those stories focused on the pending government ordinance to ban nicotine vaping products (see the ordinance here). On September 19, the World Health Organization applauded India’s official passage of that ban.

South Africa

Before March 2019, our analysis found that only three articles on “e-cigarettes” were published in the South African press. Each of those stories focused on how e-cigarettes are effective in helping smokers quit. After the US EVALI outbreak began, South African media published more and more stories on the dangers of e-cigarettes. None depicted nicotine vaping in a positive light. Nicotine “mentions spiked in August and September as the South African press carried news stories of the EVALI outbreak.

Final thoughts

Our analysis shows how the EVALI misinfodemic spread from the United States to at least three other countries. An outbreak of lung poisonings, which evidence indicates were caused by US drug dealers who mixed and sold unregulated illegal THC vaping oils, was conflated by top-tier media to implicate legal regulated nicotine vaping products in those lung injuries (see Part One of this series).

In September 2019, a fissure appeared between the two leading US public health agencies. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned against vaping THC purchased from informal sources. The CDC continued to advise against vaping both THC and e-cigarettes, although it dropped that broader advice in January 2020.

Evidence is the only effective vaccine against misinfodemics. But evidence is often uncovered too late, long after misunderstanding has spread. For example:

In 1998, The Lancet published a study suggesting a link between vaccines and autism. That paper was retracted by the journal in February 2010. But the original headlines continue to fuel an antivaxxer movement that has led to measles outbreaks around the world.

In 2019, the Journal of the American Heart Association published a study suggesting an association between e-cigarettes and heart attacks. That paper was likewise retracted in February 2020. The retraction resulted from the fact that the researchers had included nicotine vapers who had their heart attacks before vaping. Yet I continue to read references to that debunked study in the news.

In both cases, the claims made headline news. In both cases, media attention contributed to misinfodemics that spread worldwide. When the truth emerged and the studies were retracted, top tier media failed to give the retractions the coverage they warranted.

The damage was done. As Jonathan Swift wrote in 1710, “Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it, so that when men come to be undeceived, it is too late; the jest is over, and the tale hath had its effect.”

© 2023 Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. All rights reserved.